By Jack Connors

Problem Statement

Declining and unstable funding for the Milwaukee County Transit System (MCTS) has enhanced de facto segregation and worsened labor shortages in Southeast Wisconsin.

Executive Summary

For the majority of the 21st century, Milwaukee County Transit System (MCTS) has struggled financially along with Milwaukee County (Kilmer 2021). Wisconsin’s 2010-2011 biennial budget cut aid to transit systems by 10 percent statewide (Courier Staff 2011). Since then, MCTS’ lack of consistent funding has forced service cuts. Wisconsin’s legislature has become increasingly hostile towards transit in Wisconsin’s largest and most diverse city (“City of Milwaukee Comprehensive Plan” 2010). In 2021, the Wisconsin State Legislature halved transit funding solely in Milwaukee and Madison even as the state experienced an unprecedented budget surplus (MCTS Staff 2021b; Johnson 2022). To make up for this budget shortfall, Governor Evers used $19.7 million in American Rescue Plan Act funds to provide stopgap funding to MCTS (MCTS Staff 2021b). Declining shared revenue funding (unrestricted state aid) combined with limited revenue options for municipalities due to state preemption pose a fundamental threat to MCTS’ operations, exacerbate segregation, and stunt economic development. A case study of MCTS’ JobLines service illustrates the real-world implications of these policy decisions. This memo recommends that the Wisconsin State Legislature increase shared revenue funds and levy limits, reinstate municipalities’ authority to determine local sales and income taxes, and repeal the ban on regional transit authorities. On the county and local level, officials should prioritize expansion of regular service over commuter buses that primarily serve suburban residents.

Introduction Freeway construction and white flight in Milwaukee

Like many US cities, Milwaukee pursued a vast system of urban freeways in the 1960s. Between 1962 and 1967, an average of 9.5 miles of freeway were completed each year (Bessert 2021). Freeway construction paralleled white flight. Between 1959 and 1971, Milwaukee County’s freeway program displaced 6,300 housing units and nearly 20,000 Milwaukeeans (Snyder 2016, 23). From 1960 to 2000 the City of Milwaukee lost nearly a fifth of its population. Its white population fell precipitously until the 2000 Census, a clear sign of white flight (“City of Milwaukee Comprehensive Plan” 2010). Today, Milwaukee is one of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country (“City of Milwaukee Comprehensive Plan” 2010, 16; Menendian, Gambhir, and Gailes 2021).

During the Milwaukee Freeway Revolt, affluent Milwaukeeans from predominantly white areas successfully halted completion of the proposed “Downtown Loop” among other freeway expansion projects (Bessert 2021). Nonetheless, urban freeways had dramatically reshaped Milwaukee. In areas where freeway construction had not been completed, rights of way had already been cleared in many instances. For two decades, the right-of-way for the unfinished portion of the Park East Freeway sat vacant (DCD Staff n.d.).

Recent History 14 years after the Great Recession, austerity persists in Wisconsin

Under newly elected then-Governor Scott Walker, Wisconsin’s 2010-2011 biennial budget cut aid to transit systems by 10 percent statewide (Courier Staff 2011). The Walker Administration pursued drastic cuts to transit systems using austerity as a rationale. At the same time, Walker championed large highway projects. The most infamous example of this is the Zoo Interchange Project, one of the most expensive interchanges in Wisconsin history at $1.71 billion (Rast 2018, 6). In 2012, the ACLU sued the Wisconsin Department of Transportation on behalf of MICAH and the Black Health Coalition of Wisconsin, accusing the Wisconsin Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration of violating the National Environmental Policy Act by failing to consider the project’s adverse effects on low-income and minority groups who are less likely to own a car (“As Milwaukee’s JobLines Service Ends, What’s Next? | WUWM 89.7 FM – Milwaukee’s NPR” 2019). The lawsuit explicitly pointed to the project’s lack of a transit component as evidence of this (Rast 2018, 6). In 2014, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation agreed to pay $13.5 million to the Milwaukee County Transit System to settle the lawsuit. The settlement was used to fund buses, branded JobLines, between Downtown Milwaukee and two Waukesha County suburbs between 2014 and 2019 (Rast 2018, 6).

Study of JobLines riders

A study from the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s Center for Economic Development surveyed riders on two of the JobLines routes created using Zoo Interchange settlement funds. This study illustrates how declining funding for MCTS routes have exacerbated segregation and the worker shortage in Metropolitan Milwaukee. The areas served by JobLines had a much higher male unemployment rate than Milwaukee County as a whole. More than four in five riders lacked access to a car, 66 percent said they were commuters, and nearly three fourths worked outside of the City of Milwaukee. More than four out of five riders said JobLines services were “extremely important” to them getting to and holding their job and 42 percent said they would have to quit their job if services were terminated (Rast 2018, 24).

When it was operating, JobLines route 61’s ridership increased from 700 to 989 passengers, 16 percent of the suburban service area’s workforce at peak (Rast 2018, fig. 1). A University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee study recommended route 61 be considered for Bus Rapid Transit service and highlighted the need for improved transit service between Milwaukee’s inner-city and suburban ‘W.O.W.’ counties (Waukesha, Ozaukee, and Washington). Instead, JobLines service was terminated in 2018 when settlement funds were exhausted (“As Milwaukee’s JobLines Service Ends, What’s Next? | WUWM 89.7 FM – Milwaukee’s NPR” 2019).

Suburban transit options today

Today, MCTS’ fixed-route service terminates approximately five miles from where JobLine 61, the most popular JobLines route, terminated in Menominee Falls (MCTS Staff 2021c; Rast 2018, 7). This leaves JobLines’ former riders, 69.7 percent of whom were Black, just out of reach from more than 6,000 jobs in the area (Rast 2018, 16). Between 2001 and 2007, 40,000 jobs in Southeast Wisconsin became inaccessible by transit due to service cuts (MCTS Staff 2019). Service cuts in 2012 made an additional 13,553 jobs inaccessible by transit (Courier Staff 2011).

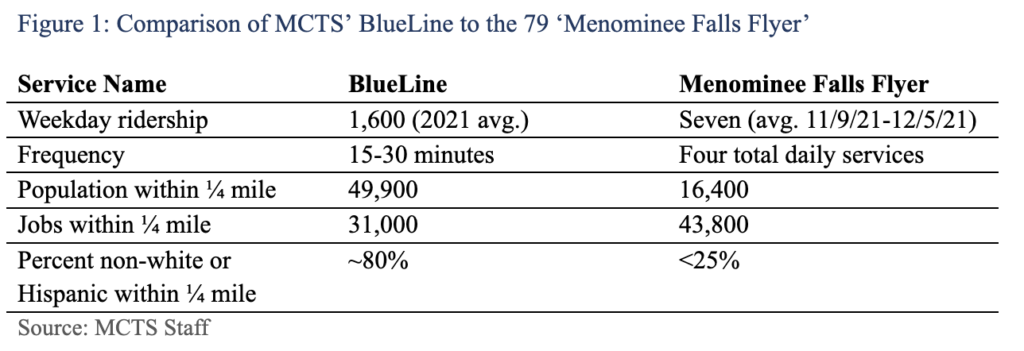

The only transit that serves the 362 employers and 6,153 jobs formally reached by JobLine 61 is the Menominee Falls Flyer 79, one of MCTS’ “Freeway Flyer” commuter bus lines that serve Metropolitan Milwaukee. The 79 is partially funded by Waukesha County and it has two morning and two evening services between Menominee Falls and Downtown Milwaukee (MCTS Staff 2022c). A 31-day premium pass for MCTS’ Freeway Flyer service is $24 more expensive than the same pass for regular service (MCTS Staff 2022a). There are 43,800 jobs and 16,400 Wisconsinites within a quarter mile of Route 79. Less than a quarter of the population within the service area is non-white and Hispanic (MCTS Staff 2021c).

The BlueLine is a regular service that connects Downtown Milwaukee to the North Side via Fond Du Lac Avenue. MCTS data found that 31,000 jobs and 49,900 Wisconsinites lie within a quarter mile of the BlueLine and almost four in five residents are non-white and Hispanic (MCTS Staff 2021c). Though JobLine 61 did not connect to Downtown Milwaukee, much of the BlueLine’s northern alignment runs roughly parallel to JobLine 61’s (Rast 2018, 8; MCTS Staff 2022b). Its average weekday ridership was 1,600 from November 9th to December 5th, 2021. The 79-commuter bus averaged seven riders over the same period (MCTS Staff 2021a).

Despite the BlueLine’s proximity to the Menominee Falls Flyer, today it would take a MCTS rider over two hours to get from the BlueLine’s terminus to the employers served by JobLine 61, it’s a seven-minute drive (“BlueLine Terminus to Former JobLine Terminus” 2022). This disparity is not uncommon, it takes 90-minutes or more to reach half of jobs in Southeastern Wisconsin (WEDC Staff 2021).

Current Considerations Apathy as Milwaukee faces mounting financial & labor issues

Increased focus on bridging the “last mile” among suburban elected officials

The BlueLine is a clear instance where transit fails to reach suburban employers to the detriment of Milwaukeeans of color. This is oftentimes called the “last mile” challenge. Recent labor shortages have renewed calls to connect Southeast Wisconsin’s suburban counties to workers by bridging the last mile—in this case five miles—between transit service and businesses.

In September of 2021, Brookfield Mayor Steve Ponto was quoted saying, “A lot of [employees] for entry-level positions do not have their own automobile or a reliable automobile and need to rely on public transportation. And right now, I know public transportation takes a long time.” Waukesha Mayor Shawn Riley lamented the fact that “municipalities, county government, the state and federal government have put all their money into the roadbeds, the off-ramps, [and] maintenance” (Quirmbach 2021).

Milwaukee County and MCTS’ worsening financial situation

Milwaukee County taxpayers have contributed an additional $355 million to the State through income and sales taxes in the last decade. Over the same period shared revenue and other funding from the state has declined or remained flat (MCTS Staff 2019). As a result, MCTS has had to cut routes and reduce frequencies in response to declining state aid that began in 2011 under then-Governor Scott Walker.

Though the first round of MCTS cuts were justified as an austerity measure in the wake of the Great Recession, funding has not recovered since. Local governments and transit providers have suffered greatly since then. Restrictions on local control greatly limited municipalities’ revenue options and the state banned the creation of regional transit authorities that facilitate cross-county transit connections (Kaiser 2013). Former Governor Walker shifted hundreds of millions of dollars away from transit providers into new capital projects for highways by moving urban public transit from the state’s transportation fund to its general fund (Crum 2011).

These projects have benefitted predominantly white suburban commuters while MCTS has been in a perpetual funding crisis. Black Milwaukeeans, who are less likely to have access to a car and more likely to use public transportation, are barred from employment and recreation opportunities beyond MCTS’ strained network (Rast 2018, 24). Even worse, Milwaukee County will have no funding for local services by 2027 (Kilmer 2021).

Recommendation Direct limited funds to expand regular service

To promote equity and address labor shortages, the legislature should restore MCTS funding above 2009 levels. Loosening levy limits, allowing local sales and income taxes, and repealing the ban on regional transportation authorities will give Southeastern Wisconsin’s stakeholders the tools to resolve MCTS’ financial issues and enhance public services broadly. Given the current makeup of the legislature, this is unlikely.

In the short-term, officials in Milwaukee and suburban counties should focus their limited resources on expanding regular service rather than commuter services like the Menominee Falls Flyer. The disparity between the jobs and population served by the BlueLine and Menominee Falls Flyer, 31,000 jobs and 49,900 Wisconsinites versus 43,800 jobs and 16,400 Wisconsinites respectively (MCTS Staff 2021c), underscores the concentration of jobs in Metropolitan Milwaukee, a legacy of white flight.

Despite serving nearly double the population area and 228 times more weekday ridership, BlueLine riders have access to just 71 percent as many jobs as the 79’s seven commuters (MCTS Staff 2021c; 2021a). Based on the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee’s 2018 survey results, a five-mile extension of the BlueLine would connect predominantly Black residents along the route to 17 percent more jobs (Rast 2018, 16). Given the challenging circumstances stakeholders in Southeastern Wisconsin are facing, it is difficult to justify expending limited resources on commuter services to a small number of suburban riders.

Conclusion Continued austerity poses a barrier to Milwaukee’s prosperity

One in five Wisconsinites live in Milwaukee County (MCTS Staff 2021b). Milwaukee’s metropolitan statistical area comprises nearly a quarter of Wisconsin’s GDP (2021; 2022). In January, the Legislative Fiscal Bureau projected that Wisconsin’s general fund will have a surplus of $3.8 billion at the end of this biennial budget period in 2023, $2.9 billion more than was projected just last year (Johnson 2022). Despite these conditions, the Wisconsin State Legislature has forced the City and County of Milwaukee to cope with austerity measures for more than a decade. The state’s actions have starved Milwaukee of the tax dollars it generates while preempting its ability to raise additional revenue. As a result, the engine of Wisconsin’s economy struggles to fund its public services even as the state experiences unprecedented surplus. Worse, this austerity has necessitated service cuts that fall hardest on Black Milwaukeeans. At the same time, investment in automobile-oriented infrastructure that benefits white suburbanites continues. In 2021, Governor Evers and the State Legislature agreed to expand a 3.4-mile segment of I-94 (Calvi 2021). By ushering in MCTS service cuts that disproportionately impact communities of color in Milwaukee, the legislature is complicit in upholding de facto segregation in Southeastern Wisconsin.

Bibliography

“As Milwaukee’s JobLines Service Ends, What’s Next? | WUWM 89.7 FM – Milwaukee’s NPR.” 2019. WUWM 89.7. August 19, 2019. https://www.wuwm.com/podcast/spotlight/2019-08-19/as-milwaukees-joblines-service-ends-whats-next.

Bessert, Christopher. 2021. “Wisconsin Highways: In Depth: Milwaukee Freeways.” Wisconsin Highways. November 7, 2021. http://www.wisconsinhighways.org/milwaukee/index.html.

“BlueLine Terminus to Former JobLine Terminus.” 2022. Google Maps. 2022. https://www.google.com/maps/dir/%E2%80%99%E2%80%99/Bradley+%26+N124,+Milwaukee,+WI+53224/@43.167503,-88.1436461,12.51z/data=!4m14!4m13!1m5!1m1!1s0x8804ff7b351b47dd:0x9efc35f3b16dee47!2m2!1d-88.1465226!2d43.1963682!1m5!1m1!1s0x8804fd893a8b153b:0xe95c007e3a7a8472!2m2!1d-88.0638488!2d43.1626562!3e3.

Calvi, Jason. 2021. “I-94 East-West Expansion Approved in Legislature-Passed Budget.” FOX6. July 1, 2021. https://www.fox6now.com/news/i-94-east-west-corridor-given-the-go-needs-legislative-approval.

“City of Milwaukee Comprehensive Plan.” 2010. Milwaukee. https://city.milwaukee.gov/ImageLibrary/Groups/cityDCD/planning/plans/Citywide/plan/Data.pdf.

Courier Staff. 2011. “Cuts in Transit Could Add to Poverty Levels in Milwaukee – Milwaukee Courier Weekly Newspaper.” Milwaukee Courier. October 8, 2011. https://milwaukeecourieronline.com/index.php/2011/10/08/cuts-in-transit-could-add-to-poverty-levels-in-milwaukee/.

Crum, Kieth. 2011. “Walker’s Budget Guts Transit.” Milwaukee Transit Riders Union. 2011. http://www.transitridersunion.org/news/walkers-budget-guts-transit.

DCD Staff. n.d. “Park East History.” City of Milwaukee Department of City Development. Accessed April 7, 2022. https://city.milwaukee.gov/DCD/Projects/ParkEastredevelopment/Park-East-History.

“Gross Domestic Product: All Industry Total in Wisconsin (WINGSP) | FRED | St. Louis Fed.” 2022. St. Louis Fed. March 31, 2022. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/WINGSP.

Johnson, Shawn. 2022. “Wisconsin Budget Balance Now Projected at $3.8B | Wisconsin Public Radio.” Wisconsin Public Radio. January 25, 2022. https://www.wpr.org/wisconsin-budget-balance-now-projected-3-8b.

Kaiser, Lisa. 2013. “Is Scott Walker Killing Off Public Transit? | WISPIRG.” Milwaukee Shepard Express. March 6, 2013. https://wispirg.org/media/wip/scott-walker-killing-public-transit.

Kilmer, Graham. 2021. “MKE County: County Faces Financial Disaster.” Urban Milwaukee. May 3, 2021. https://urbanmilwaukee.com/2021/05/03/mke-county-county-faces-financial-disaster/.

MCTS Staff. 2019. “Proposed 2020 Transit Budget Includes Significant Service Changes.” MCTS. August 13, 2019. https://www.ridemcts.com/who-we-are/news/proposed-2020-budget.

———. 2021a. “MCTS Fall 2021 Quarter Ridership.”

———. 2021b. “Governor Evers Partially Restores Funding Gap for Transit in Milwaukee County.” August 30, 2021. https://www.ridemcts.com/who-we-are/news/governor-evers-partially-restores-funding-gap.

———. 2021c. “Fall 2021 Current System for RideMCTS.Com – Remix.” Remix.Com. September 2021. https://platform.remix.com/map/4efab8a8?latlng=43.05734,-87.96995,10.28&public=true.

———. 2022a. “Fares & Passes.” MCTS. 2022. https://www.ridemcts.com/fares-passes#passes.

———. 2022b. “Ride MCTS | BlueLine: Fond Du Lac – National.” MCTS. 2022. https://www.ridemcts.com/routes-schedules/blueline.

———. 2022c. “Route 79.” MCTS. 2022. https://www.ridemcts.com/routes-schedules/79.

Menendian, Stephen, Samir Gambhir, and Arthur Gailes. 2021. “The Roots of Structural Racism Project | Othering & Belonging Institute.” UC Berkeley Othering & Belonging Institute. June 30, 2021. https://belonging.berkeley.edu/roots-structural-racism.

Quirmbach, Chuck. 2021. “Some Milwaukee Suburbs Want More Mass Transit, Amid A History Of Race and Political Controversies | WUWM 89.7 FM – Milwaukee’s NPR.” WUWM 89.7. September 29, 2021. https://www.wuwm.com/2021-09-29/some-milwaukee-suburbs-want-more-mass-transit-amid-a-history-of-race-and-political-controversies.

Rast, Joel. 2018. “JobLines An Analysis of Milwaukee County Transit System Routes 6 and 61.” Center for Economic Development University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Milwaukee. www.ced.uwm.edu.

Snyder, Alex. 2016. “Freeway Removal in Milwaukee: Three Case Studies.” Theses and Dissertations. May 1, 2016. https://dc.uwm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2254&context=etd.

“Total Real Gross Domestic Product for Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI (MSA) (RGMP33340) | FRED | St. Louis Fed.” 2021. St. Louis Fed. December 8, 2021. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/RGMP33340.

WEDC Staff. 2021. “Connecting Workers with Jobs in Southeast Wisconsin | WEDC.” WEDC Blog. 2021. https://wedc.org/blog/connecting-workers-with-jobs-in-southeast-wisconsin/.